When I was a kid, pretty much all baseball players were model citizens. We knew this because the sports pages told us so. Day after day, sportswriters informed us that these athletes were shining beacons of moral goodness, a credit to their teams and communities, and the kind of people who boys like me would do well to emulate.

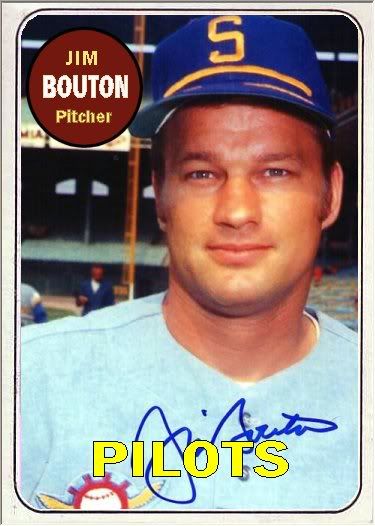

Jim Bouton put an end to that. I read Ball Four, Bouton’s magnum opus about what professional baseball really was like, when I was 12 or so. That’s when I learned that lots of baseball players lie, cheat on their wives, drink to excess, pop amphetamines like Chiclets, have the overall moral turpitude of a creepy guy in a trench coat — and, in that pre-union era, were treated like chattel by short-sighted, cheapskate owners.

The book also was funny. Achingly funny. Stop-and-grab-your-sides funny. But there was a pathos underneath it, as Bouton outlined his struggles to maintain his career as a professional baseball player. He was a knuckleball-throwing reliever who, in the season documented in the book, bounced between the now-gone Seattle Pilots of the American League, a minor league club, and the Houston Astros. He kept a diary of his experience, which became the basis for the book.

When Ball Four came out, you would have thought Bouton was dealing drugs to toddlers based on the amount of outrage it generated. Old-school sportswriters, used to living cushy lives in exchange for not reporting on what players did off the field, looked like fools and acted like bullies in response (a trait shared to this day by the biggest hacks in the field, I’d note). A lot of players went completely ballistic as their trade secrets were exposed and their spouses started asking way too many questions.

And Ball Four became a huge best-seller. Kids like me lapped it up, and so did plenty of other people.

My friends and I all started quoting lines from Joe Shultz, the Pilots’ manager. Bouton portrayed him as a good-natured semi-dolt who motivated players by pointing out that, once the game was over, they could all pound some Budweisers in the clubhouse. “Hija, blondie. How’s the old tomato?” Schultz once asked a woman he spotted in the stands (or so Bouton claimed).

“Ball Four” was full of gutter talk like that, and pervy acts involving players and baseball groupies. A lot of this could make me a little embarrassed today, but I found it super-fascinating at the time because…well, tween boy.

For example, the fact that players loved staying in L-shaped hotel buildings for the viewing-into-other-rooms opportunities they provided was not something that had occurred to me. Comparing detailed thoughts about women in the stands — or the women they were with the night before — while burning time in the dugout was not the kind of game-only focus I thought my heroes experienced.

The book outlined practical jokes involving Icy Hot balm in jockstraps and talcum powder in hair dryers. Bouton claimed Whitey Ford (I think) once raffled off a ham in the clubhouse, but there was no ham and no winner. This was just one of the risks of a game of chance, Ford explained.

Post-Ball Four, Bouton became a pariah to many players, but a hero to many of us. He parlayed the experience into a post-baseball career as a sportscaster, writer, actor, investor and more. The phony sheen over baseball players — and the owners who abused them — was pulled away forever, to what I’d claim was the benefit of everyone. Sportswriters had to act like journalists instead of team employees.

The game, stripped of this phony nonsense, exploded in popularity. Players banded together and got paid. And a whole new genre of tell-all sports books (none as good as this one, but some nonetheless enjoyable) was spawned.

Bouton died earlier this week. He was 80. I think I’ll read Ball Four again if I can find a copy.